With a column name like mine, you might think I’d have a lot to say about the new Gaza war. How different could it be from the other wars that obsess me? But just typing that question feels absurd. None of it —my absorption in U. S. military history and book about those who shaped it like those above, my work on current imbroglios with the Center on Conscience and War and the Military Law Task Force , let alone my glance at medieval warfare for my magical-realist take on Joan of Arc—could help me make sense of this month’s existential crisis :drowned in blood.

Neither could my own memories of going to Palestine in 1990, when an Israeli Defense Force officer told a Palestinian student, “You know wat the Germans did to my people? That is what we are doing to you.”

Like you, perhaps, I’ve spent much of the time since October 7 reading take after take, hoping for some kind of guidance. Here are some I found useful.

Sarah Schulman in New York Magazine, about growing up Jewish in New York when Israel was a precious dream for her family: “They could not adjust the worldview born of this experience to a new reality: that in Israel, we Jews had acquired state power and built a highly funded militarized society, and were nw subordinating others. No one wants to think about themselves that way. As a Jew and an American who has gone through the complex, painful, and transforming process of facing the injustice against Palestinians committed in my hname and with my tax dollars, I have had to change my self-concept. I have had to deprogram myself from the idea that Jews continued to be victims when, in some cases, we had become perpetrators.”

Similarly, in Jewish Currents Arielle Angel writes, “In ts his way, Jewish grief is routed back into the violence of a merciless system of Palestinian subjugation that reigns from the river to the sea.”

As a non-Jewish peace activist who nonetheless grew up in with the same ideal of Israel Shulman did but faced the reality of the occupation in 1990, I first went to War Resisters International’s statement calling on both sides to stop the violence.

And as a fan of soldier-dissenters, I’m glad that Avner Gvayahu of Breaking the Silence was featured in the New Yorker’s The Tangled Grief of Israel’s Anti-Occupation Activists:

“This is a real moment of no return,” Gvaryahu said. “I don’t think anything will be the same.” This is the one analytical idea that most Israelis can agree on right now. They interpret it differently, though. “The right expects us to say that we were wrong,” Scheindlin said. “That we were wrong to think we can make peace with the Palestinians. That we were wrong to think we can live with the Palestinians. That we were wrong to see them as equals.”

In fact, anti-occupation activists on the left such as Gvaryahu believe that they were right. “This proves a lot of what we’ve been trying to highlight,” he told me. “That you can’t ignore what’s happening in the Gaza Strip, that it’s not some ex-territory.” Israeli human-rights activists had long said that maintaining Gaza as an open-air prison was not only inhumane toward the residents of Gaza but also a security risk for the region. “We’ve warned for a long time,” Michaeli agreed. “But, when it actually happens, it’s the most devastating thing.” \

In Waging Nonviolence, Matt Meyer of the International Peace Research Association writes that instead of feeling helpless, each of us needs to taking our part in building the 21st-century’s anti-apartheid movement. “Let us do much more than write statements, spout rhetoric, and/or line up to be in one small camp or another. Solidarity will inevitably be expressed in different ways by those who have differing views on resistance.”

For writers like me, that means telling stories that make a difference. I’m guided by my friend Alice Sparberg Alexiou and her piece “Fanny in Ottoman Jerusalem,” in the Fall issue of New England Review. Jerusalem before and during World War I, the fascinating backdrop to the story of Alice’s ancestor, provides a glimpse of an accidentally multicultural past, very different from those trumpeted by either Israeli or Palestinian sources. I can’t wait for Alice’s book on the subject but the NER piece is fantastic. (It’s not an online magazine; at the link you can order a copy of the issue, or wait for an excerpt on LitHub.com.) The complexity of history and of people’s complex lives: those should anchor us and our dialogues, always.

Next weekend I’m going to the 2023 Peace History Society conference, which will contain presentations about Ukraine but not yet Gaza; I wonder what hallway conversations will be like. I hope they contain some of that complexity.

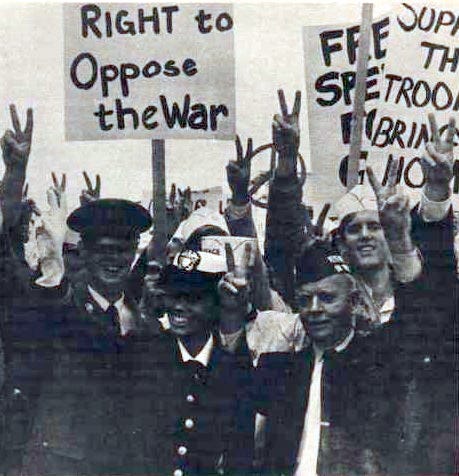

(Photo: Lieutenant Susan Schnall, Brigadier General Hugh B. Hester and Airman Michael Locks marching in GIs and Veterans for Peach march October 12, 1968. Wikimedia Commons)

That collection of voices offers clarity and insight that we badly need right now.

THIS NPR piece is extraordinary-- as are the individuals and communities profiled. Including the doctor who started Parents Circle: "Damelin has also helped run a summer camp for bereaved Palestinian and Israeli teens. One of her own grandchildren attended and told her, "This is the best week that I've ever spent in my life."

https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2023/11/05/1209976575/israel-hamas-war-hope-empathy-personal-stories